On May 1, 2025, the U.S. House of Representatives passed resolutions ostensibly pursuant to the authority provided in the Congressional Review Act1 in an attempt to block implementation of California’s vehicle emissions mandates, including the Advanced Clean Trucks regulations and Advanced Clean Cars II regulations. The target of the House resolutions is the Biden Administration’s December 18, 2024, approval of the Clean Air Act waiver allowing California to begin full implementation of its regulations.2

California’s Advanced Clean Truck Regulations, Governor Newsom’s Proposed Ban, and the Advanced Clean Cars II Regulation.

California promulgated its unique vehicle emission standards pursuant to the “waiver” provisions of the federal Clean Air Act.

California’s Advanced Clean Truck Regulation requires manufacturers of medium and heavy-duty trucks to sell an increasing percentage of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) annually, starting with the 2024 model year. The rule is designed to reduce tailpipe emissions from trucks, particularly in the freight industry.

In 2020, as part of an effort to lower emissions from the transportation sector and transition away from fossil fuels, Governor Gavin Newsom in Executive Order N-79-20 announced plans to ban the sale of all new gas-powered vehicles in the state by 2035. Plug-in hybrids and used gas cars still could be sold. State regulators then formalized the proposed rules in 2022. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) adopted the Advanced Clean Cars II regulations (ACC II) that are designed to reduce motor vehicle emissions of criteria pollutants and greenhouse gases. ACC II modifies the Low-Emission Vehicle Program and Zero-Emission Vehicle Program. The ACC II regulations begin with vehicle model year 2026.

Specifically, ACC II mandates that by 2035, 100% of new light- and medium-duty vehicle sales in California must be either ZEVs or plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs).

California’s Vehicle Emissions Waiver is Unique. But, in 1990, Congress Allowed the Other States to Join in the Action.

The Clean Air Act (CAA) 42 U.S.C. §§7401 et seq., preempts state governments from adopting their own air emissions standards for new motor vehicles and new motor vehicle engines. But Congress exempted California. Under CAA section 209, California can apply to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for a waiver from the federal preemption. The EPA must grant this waiver absent certain disqualifying conditions.

Section 209(b) of the CAA Section provides that:

[t]he [EPA] Administrator shall, after notice and opportunity for public hearing, waive application of this section [the preemption of State emissions standards] to any State which has adopted standards (other than crankcase emission standards) for the control of emissions from new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines prior to March 30, 1966, if the State determines that the State standards will be, in the aggregate, at least as protective of public health and welfare as applicable Federal standards.

Only California can qualify for the preemption waiver because it is the only state that adopted new motor vehicle emissions standards prior to March 30, 1966.

The EPA must grant the waiver absent certain disqualifying conditions listed in section 209(b):

- The determination of the state is arbitrary and capricious;

- Such state does not need such state standards to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions; or

- Such state standards and accompanying enforcement procedures are not consistent with Section 202(a) of the CAA.

If the EPA determines that any of these three conditions are not met, it must deny California’s request for a waiver.

California vehicle emissions standards must meet or exceed federal emission regulations. Since the enactment of the CAA, the CARB has requested and received over 100 waivers.

The Section 177 States

Although states other than California are not permitted to develop their own emissions standards, in 1990, Congress amended the CAA adding section 177 that authorizes other states (and the District of Columbia) to adopt some or all of California’s standards in lieu of federal requirements. Importantly, the so-called “Section 177 States” are not required to seek EPA approval before adopting California’s standards.

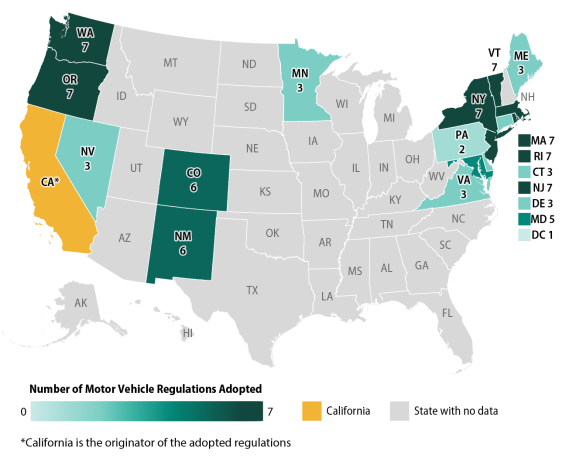

In addition to the District of Columbia, the map3 below shows the 17 “Section 177 States”:

Additional California Waiver Requests Pending

As of August 2024, California had seven waiver or authorization requests pending EPA action: the Heavy-Duty Omnibus Low NOx (nitrogen oxide) waiver, Small Off-Road Engine authorization, Transport Refrigeration Unit authorization, ACC II waiver, In-Use Off-Road Diesel-Fueled Fleets authorization, In-Use Locomotive authorization, and Advanced Clean Fleets waiver.

Does the Congressional Review Act Give Congress Authority to Disapprove the Waiver?

The House resolutions were adopted essentially along party lines with 35 Democrats agreeing to advance them. The House enacted the resolutions ostensibly pursuant to the authority of the Congressional Review Act (CRA) with the goal of overturning the Biden Administration’s CAA California waiver.

The CRA and “New” Rules. The CRA, enacted in 1996 during the Clinton Administration to strengthen congressional oversight of agency rulemaking, requires federal agencies to submit a report on each new rule to both houses of Congress and the Comptroller General for review before the rule can take effect. 5 U.S.C. § 801(a)(1)(A). The report must contain a copy of the rule, “a concise general statement relating to the rule,” and the rule’s proposed effective date.

The CRA allows Congress to review and disapprove rules issued by federal agencies for a period of 60 days using special procedures. See 5 U.S.C. § 802. If a resolution of disapproval is enacted, then the new rule has no force or effect. 5 U.S.C. § 801(b)(1).

The CRA’s Lookback Period. In addition to authorizing Congress to address “new rules,” the CRA gives Congress the authority to address rules that had been promulgated in the 60 “working days”4 before the end of a session of Congress through the beginning of the next session of Congress. It is this “lookback period” provision that has triggered the most action under the statute during the transition from one administration to the next.

Through August 2024, the CRA has been used to overturn a total of 20 rules: one in the 107th Congress (2001-2002) (the transition from President Clinton to President Bush); 16 in the 115th Congress (2017-2018) (the transition from President Obama to President Trump); and three in the 117th Congress (2021-2022) (the transition from President Trump to President Biden).

Since the election in 2024, the new Congress has used the “lookback period” provision in a series of exceptionally aggressive challenges to agency rulemaking. Since the beginning of the 119th Congress (January 1, 2025), 60 joint resolutions have been introduced pursuant to the CRA. These resolutions target rules from 24 federal agencies, with the EPA being the most frequently targeted.5

The GAO Legal Opinion re: the Biden California Waiver. The May 1, 2025, House resolutions were approved against the advice of the Senate Parliamentarian who agreed with the position taken by the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) in its March 6, 2025, letter to Congress.

The letter reiterated the GAO’s legal decision that was originally issued in 2023 concluding that California’s policies are not subject to the review mechanism provided in the CRA because the CAA waivers are not “rules” as defined by the statute but are technically only an “adjudicatory order” granted by the EPA under the Administrative Procedures Act (APA).

Specifically, the GAO letter was in response to a request from Senators Sheldon Whitehouse, Alex Padilla, and Adam B. Schiff for a legal decision in the matter. The GAO prefaced its analysis stating:

Our regular practice is to issue decisions on actions that agencies have not submitted to Congress as rules under CRA in order to further the purposes of CRA by protecting Congress’s CRA review and oversight authorities. In this case, we are presented with a different situation because the actions were submitted as rules under the CRA, and it is not one in which we normally issue a legal decision. However, we do have prior caselaw that addressed the applicability of CRA to Clean Air Act preemption waivers, B-334309, Nov. 30, 2023, and EPA’s recent submission is inconsistent with this caselaw. Therefore, we are providing you with our views and analysis of preemption waivers under the Clean Air Act that may be helpful as Congress considers how to treat these Notices of Decision and the application of CRA procedures.

After an extensive analysis of the CAA preemption waivers, the Notices of Decision that the EPA submitted as “rules to Congress” and the limitations of the CRA, the GAO concluded in its letter to Congress:

In these circumstances, our view is that our prior analysis and conclusion in B-334309 that the Advanced Clean Car Program Waiver Notice was not a rule for purposes of CRA because it was an order under APA would apply to the three notices at issue here.

Now Over to the Senate (And the Courts?)

It is unclear what will happen in the Senate. In April, the Senate Parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, reaffirmed the GAO’s findings that California’s CAA waivers are not subject to the CRA because they do not constitute “rules” subject to the CRA process.

As of this publishing, the U.S. Senate has not acted on the CRA resolutions. However, in light of the 60-day window provided in the CRA, action will have to come before June 1. Because the House of Representatives has already voted to overturn the waivers, the Senate has 60 days from that vote to decide whether to follow suit. If the Senate fails to act by June 1, the waivers will remain in effect.

And even if the Senate approves the resolutions, the legal question as to whether the Congress is acting properly pursuant to the authority of the CRA would undoubtedly end up in court.

This blog was drafted by John L. Watson, an attorney in the Spencer Fane Denver, Colorado, office. For more information, visit www.spencerfane.com.

—

1 See summary of Congressional Review Act here.

2 See Congressional Research Service FAQs re: the Clean Air Act waiver.

3 Congressional Research Service, with data from California Air Resources Board, “States That Have Adopted California’s Vehicle Regulations,” https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/advanced-clean-cars-program/states-have-adopted-californias-vehicle-regulations

4 “60 working days” refers to either 60 session days in the Senate, or 60 legislative days in the House.

5 See “Congressional Review Act – Overview and Tracking,” National Conference of State Legislators.

Click here to subscribe to Spencer Fane communications to ensure you receive timely updates like this directly in your inbox.